The CEO’s mission is to make sure his enterprise is ever flourishing. The criterion for ever-flourishing companies is to grow and be profitable far into the future, to always satisfy their customers and, achieve and maintain both satisfying and secure jobs for their employees.

The CEO mission is easy to define but it is an extremely challenging target. What should CEOs concern themselves with in order to achieve this very ambitious target?

Make Money Now and More in the Future

What is the key factor that blocks a CEO’s business from making more money? What might the core problem be that leads a newspaper like the Guardian to write t

hat senior executive remuneration is absurdly high and that many of those chosen for top jobs are ‘mediocre’?

A lack of intelligence cannot be the core problem – almost all senior executives are very smart. Their results or their performance may be mediocre, but intelligence, they do not lack. So, what blocks their performance, and what blocks their companies from achieving more of their targets?

What is a CEO’s mission?

Whatever vision, mission or goal an organisation (a business) has, it cannot pursue it without sufficient money. Cash flow, profit and return on investment now and more in the future are essential for any enterprise to flourish. It is obvious this necessary condition must be fulfilled, along with satisfying customers and ensuring satisfying and secure jobs for employees. What is not so easy is to fulfil are all three necessary conditions at the same time, forever. To fulfil them is, however, the mission of every CEO and his management team.

Initially my focus will be on the first necessary condition for success – to ensure growing cash flow, profit and return on investment. (If a CEO can generate enough cash flow, profit and ROI, without alienating his team, he will have the means to pursue the other two necessary conditions.) To focus on the bottom line a CEO must first be dissatisfied with his company’s current levels of cash flow, profit and return on investment (independent of the glowing reports found in the annual report).

What blocks Businesses from making more Money?

(Now and in the Future)

The core of this CEO problem and for almost all businesses is an, apparently, wrong assumption about what a business is. On the one hand all managers know that a business is a system of interdependent departments, divisions and groups. On the other hand many policies, reports and key performance indicators (KPIs) are aimed at one department or division at a time; most policies, reports and KPIs focus on the decisions and actions of one or at best just a few departments. The way a business is managed is therefore at the local level; as though departments and divisions are independent of each other – the actions of one, it is implicitly assumed, does not affect the performance of another. Every manager and department is asked to focus on his local environment to improve it. Local optimisation is the rule; global optimisation, unfortunately, is not.

The World is not quite so black and white. Most business is managed by some sort of a compromise – a bit of global optimisation and a bit of local optimisation. I believe local optimisation is, in fact, the way most businesses operate most of the time. Are such compromises the right way to operate? What is the cost of compromise to the bottom line? To begin to find out the cost of these compromises, what does the dilemma or conflict, the reason for compromise, actually look like?

It is probably safe to assume that CEOs, and his managers, want to lead their company to become an ever flourishing one, now and even more so in the future.

To achieve this the CEO needs, on the one hand, a set of simple policies and key performance indicators (KPIs) to guide all levels of managers and employees to make good decisions for their division, department or area – the manager’s area or responsibility and expertise. These departments must be competent effective and efficient in what they do – be it production, research and development, sales or any other function. The CEO needs departments that all do an excellent job in their area of responsibility – he expects them to optimise locally. This side of the conflict is usually managers’ focus.

On the other hand departments are interdependent. To deliver the desired bottom line result they must work together in an aligned and coordinated way. It is very easy for any department to take a decision that on the surface seems to make a lot of sense but, when the decided action is taken, damage to another department’s performance is the consequence. Whenever this happens the company’s bottom line is at risk – actually the bottom line usually suffers. Instead the CEO needs all departments to optimise in a way that does not damage those few factors (production capacity, or market demand for the company’s products, …) that limit the bottom line. The CEO not only needs his department managers to keep the bottom line in mind, but he needs them to act in a way that optimizes the bottom line. He needs his department managers to be an integral part of the company’s global optimization.

Departments should therefore optimize both locally and globally, at the same time. To do this will certainly trigger conflicts within and between departments depending on how each individual department or division is measured. On the surface it’s an easy decision to optimize globally – the rule would be to, “always do what is good for the company as a whole”. Under the surface, within all the departments, the situation is as clear as mud! How can a manager somewhere within the company have enough knowledge and insight into the workings of the company to always be in a position to take the right decision? ERP systems may have the necessary data within them; the necessary information is not generated and does not reach the managers that need it.

The following diagram describes the conflict:

As described above both needs are valid; for the company it is important that both are fulfilled.

The wants are in conflict. It is apparent both wants cannot easily be achieved concurrently. The Wants are in conflict but that should not be the situation because both the Wants are there to fulfil an important valid need.

What are my assumptions for the reasons the two Wants are in conflict? There are several and you may find more:

- Very often top management’s KPIs are in conflict with local department or divisional KPIs.

- In most companies managers at the local level do not have the necessary information to be able to make the right decisions for the company as a whole. Usually the information available to them is only about their immediate environment.

- ERP systems, despite the huge amounts of data they contain, do not supply the necessary information for managers at all levels to take the right decisions for the company as a whole.

- In many companies policies, rules, culture and organisation structures exist that lead to conflict situations between departments.

These 4 are possible explanations for the CEO’s problem (or conflict) over global vs. local optimisation. 4 Examples may illustrate the situation better.

1. Top management’s KPIs are in conflict with local KPIs:

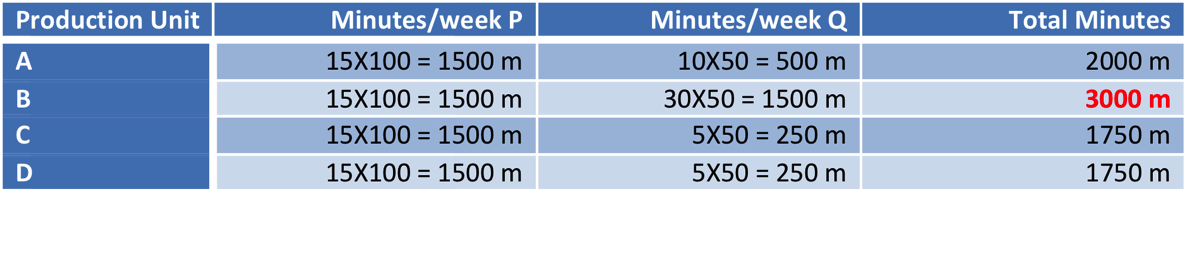

Top management KPIs are things like cash flow, profit, ROI coupled with things like the per cent of sales and profit that comes from the last 3 years’ new product introductions. On the other hand at the local level departments like R&D or production have efficiency or cost reduction KPIs. Efficiency or cost KPIs will usually cause managers to make sure all resources are all working productively. The consequence of efficiency as a goal is often factory overload (very high work-in-process levels) leading to both high inventory levels and shortages (because switching between products lowers efficiency) and ultimately damage to CEO KPIs. Inventory levels, profits, cash flow and return on investment are all impacted negatively.

In R&D the need for efficiency causes managers to launch too many projects in an effort to keep everyone busy (and ‘effective’). The consequence, as shown by Little’s law, is both a loss of capacity and of speed. Both losses impact hurt the CEO’s bottom line.

The graphic to the right illustrates the situation. Many (most) companies operate in the pink ‘common practice’ area and suffer the consequences in longer lead-times, reduced capacity and as a result of these 2 effects poor due date performance. The problem stems from KPIs, like efficiency, which cause departments[1] to overload their resources as the graphic shows.

The impact of lost sales due to overloading production can be enormous. By moving from too much WIP to the sweet spot a company can produce additional volumes without adding any cost. If this added production could be sold the impact to the bottom line is sales less (just) materials cost – a major incremental benefit. Just 10% more sales increases a 6% bottom line to about 11% (assuming materials are 50% of sales). This is huge!

It is part of the CEOs mission to make sure local KPIs (that he and his management team set or agree to) do not damage his (and the company’s) KPIs!

2. Local Managers do not have access to the Right Information!

Aramid fibres are used in many applications from tire reinforcement, to reinforcement for optical glass fibres, to sailcloth, ropes, filtration and more applications. Fibres such as Aramids are produced in many different fibre diameters (the unit of measure is decitex – the grams of fibre per 10’000m). In the factory the limitation in terms of kilos produced depends either on the flow of polymer or the flow of fibre in the spinning process.

In the businesses concerned each application is a profit centre and all of them compete for product from the same factory. All have different profit margins based on calculated production costs and the market prices. If the factory is sold out –all of the profit centres will fight to get enough to meet their demand and fulfil their forecasts. But which of the profit centres should be favoured in order to maximise the overall business profit?

Should the fine decitex products that have much higher margins vs. the heavy decitex products be favoured? Is the profit margin the right criterion? If not, what is, and do the profit centres get the appropriate right guidance?

In this case all the managers have are profit margin and contribution (sales less materials cost) margins. But, when the factory is sold out, this is not enough. They need to know how effectively, in terms of the bottom line, the factory’s capacity is used; they need the contribution per machine hour (or, possibly, factory hour). This is the absolute margin earned by a product (or sale) per hour of the constraint machine (or factory). A fine decitex takes a long time to earn its margin while a heavy one earns it quickly. Without this sort of information the profit centres are likely to make the (common) error of preferentially selling the apparently high margin product that actually delivers less to the bottom line.

For the CEO to fulfil his mission he must make sure profit centres have the right information at the right time (a factory is not usually sold out all the time). His profit centre managers must be in the position to maximise the Throughput (the same as contribution used above) of the constraining element (for the company as a whole). To do this he needs those people with the capability to develop the necessary KPIs that truly align every profit centre with a CEO’s bottom line targets.

The example talks to the need for sales to sell the right products to maximise Throughput. There are other situations that need proper clarification and better information for managers to take the right decisions.

In many (most?) instances managers of a department have no choice but to optimise locally; they simply do not have the necessary information and decision rules to operate any differently.

(Industry 4.0 is coming. Will it solve this problem? The potential exists but a big part of making Industry 4.0 a success is the necessary change to management practice.)

3. ERP systems are no help; but they could be!

There are many examples of situations such as that described in the section above. The data necessary to generate the required information for the right decisions exists, to a large extent, within ERP systems. The necessary information could be made available but generally common practice prevents its generation. Is the view is not worth the climb? The example about misaligned KPIs should be powerful enough to at least indicate to CEOs that the potential is or can be huge. CEOs have the power to cause the necessary upgrades to their ERP systems and make the right information available for all those managers and employees that could make good use of it.

Employees will be a problem. For so long, their only option has been to optimise locally. They probably have (very) little aptitude and knowledge how to think about the company as a whole – let alone evaluate their local action’s impact on the company. Whenever I ask a manager about another part of the company I get either no answer or some sort of wild guess. Its very much like most of the World’s population that, despite the best efforts of the BBC, CNN and others, has no idea what its really like to live and work in other countries. The CEO’s job will be to get everyone into the new mind-set (or new paradigm); one that requires all of us to understand our roles for and our impacts on the company as a whole.

The concepts are not difficult to grasp – they are (just) common sense. Nevertheless managers at all levels will need coaching to get them over the hump so that they can always decide in favour of the company. Inertia is the barrier to rapid and sustainable change because once something is learned it becomes a paradigm and is then difficult to shift. Old paradigms must be shifted and not just by a little bit. CEO’s have it in their power to cause paradigm shifts – by leading the change together with their C-level colleagues. The C-level team’s leadership is key for the necessary change.

4. Assumptions, Policies, Rules, KPIs, Culture, Structure

A CEO arrives in his job with experience, knowledge, a set of assumptions, and paradigms he acquired in his previous jobs. All of these are obstacles to change because paradigms are generally not questioned – there is simply not enough time in a day or month to question them all since a CEO has so many things that concern him. He is bombarded with problems and decisions from both internal and external sources – not to mention the various official duties he may have. A CEO solves, somehow, conflicts such as what products should be sold – to optimise production or to generate the highest sales volumes and margins. Often such problems are solved with a (less than optimal) compromise because both departments get half a win. In the end nobody is truly satisfied.

If a CEO solves such a problem in the way just described he is likely following an assumption about the importance of maintaining motivation; although I wonder how motivating such compromises really are since ‘in the end neither department can be satisfied’.

The important word is assumption. Based on what he knows the CEO has a collection of assumptions (or paradigms) that determine how he will behave. His paradigms are the necessary shortcut essential for him to manage given the stresses and volume of work he faces. Without them his job would, for time reasons, be impossible. With paradigms, especially if their validities are not questioned, his mission is just as impossible to achieve because many paradigms, if not wrong, are inadequate for his job. He cannot achieve his mission.

On his own a CEO cannot develop the appropriate policies and KPIs – he is too busy. He needs someone that understands the need for and how to get global optimisation. He must give this person the freedom and necessary time to craft both the new policies and the related KPIs. The management team and the company as a whole must review these KPIs – do they really support the company as a whole; do they give the correct guidance to all departments? Everyone should have the possibility to input from their different perspectives in order to test the new policies that should guide the company to optimise globally, and leave local department optimisation behind.

Products and Services are “Created Equal”

What our competitors and our company offer to customers is all about the same. In most cases not one of the competitors in our industry has a sufficient enough competitive advantage to gain market share or to realise better prices. All of us suffer declining prices as our customers take advantage of this situation. We all have no choice but to match ever-lower prices in order to maintain market share and contribution to our bottom line. More and more our focus is cost and efficiency. We are forced to reduce cost to survive with ever-thinner margins. More and more our ability to invest in the future through better (production) equipment and new products is compromised. Without a miracle we may soon be out of business.

This sounds dire. It is probably the truth in more industries than we think. Look at Apple and Samsung smartphones. Are they, in reality, much different one from the other? For the average user it probably makes no practical difference which smartphone he or she has. For most other industries the differences between products is probably even smaller than this example. Product differentiation is often not the key factor to gain market share. In most industries, if a product differentiation is achieved, competitors will almost always catch up very quickly.

How can your company achieve a decisive or (even better) several decisive competitive advantages so that your (the CEO) can achieve his mission – a truly ever-flourishing business? The answer must come from effectiveness, speed and reliability from the company’s key departments.

Finance, Key Performance Indicators and Policies

Cost Reduction

A consequence of the described situation is pressure on cost (by Finance). Clearly every bit of cost we can eliminate from our operating expenses will help improve the bottom line. True, if the cost reduction does not cause Throughput[2] (or sales) to decline. If Throughput declines the effect of a cost reduction can easily be negative – for every sale lost the corresponding Throughput (or contribution margin) will be lost from the bottom line. (A 5% turnover loss wipes out a 5% cost reduction for a typical company.)

Common practice favours cost reduction over the possible (but uncertain) impact on sales and Throughput. Maybe this is because we can define exactly the cost to be reduced (the advertising we stop, the people we fire etc.) while it is very difficult to predict the impact on sales and the reasons for this sales impact. Nevertheless Throughput is very real and somebody must make the judgement call of any decisions impact on Throughput and therefore on the bottom line.

We recommend companies to look at a contemplated decision’s impact in absolute numbers – sales, Throughput, operating expenses and profit. The CEO’s role and responsibility is to make sure Finance and the company’s managers evaluate their decisions based on the effect on Throughput, Operating Expenses and Investment, not just the impact on one department! Following this recommendation will tend to help a company maintain and even increase market share. It will help the company focus more on those things that do increase sales and market share. It does not diminish the importance of cost; it does increase the importance of Throughput and Inventory relative to cost.

Efficiency

All managers want to apply their resources efficiently. “A resource standing idle is a major waste”; so managers will try to make sure everyone is busy working on something (at least apparently) useful. Concurrently all employees will want to be busy – after all they are as aware of cost pressures as managers. If employees are not busy (not seen to be busy) then they feel their jobs are no longer secure.

The damaging consequence of everyone and every machine working “all of the time” is factories to fill up with work in process that will slow the production process down, make the factory unreliable and deteriorate quality. The chaos that reigns on the shop floor reduces a factory’s capacity and correspondingly increases unit costs – especially as sales are lost due to longer lead-times and greater unreliability.

The CEO’s role is to make sure work in process is never above the optimal range that ensures lead-times are low, production can deliver reliably on time and capacity is maximised. If a CEO is able to do this, his company will eventually gain sales and market share with little or no added cost. Share gains have the added benefit of weakening the competition. Good reliability and shorter lead-times also will result in less price pressure from the market. This advice (ensure the optimal level of work in process[3]) holds true for all areas of a business – not just production.

Efficiency is often measured based on tons/hour (steel); square meters per hour (films, paper; units per hour etc.) or, in the case of sales, the number of calls sales people make. In the good old days of X-Ray film production factories produced film large enough to X-Ray an entire thorax as well as tiny films for dentists to X-Ray your teeth. Factories measured production efficiency by the number of m2 produced in a shift. Since film for dentists was (is) inefficient to produce, production supervisors would postpone dentistry film for the next shift or until someone started yelling very loudly! In steel factories thick steel plate is much more ‘efficient’ to produce (in tons/hour) than thin plates – so there is usually a surplus of thick and shortages of thin plates.

The CEO’s role is to make sure the load on a factory is limited to a maximum amount where production capability and lead-times are optimal, and there should be no more in stock than required for the near future. Production must not steal capacity from one product in order to produce too much of another. To produce more than immediately necessary might improve efficiency numbers, but it often steals capacity required for (much) more urgent and real demand.

Efficiency is important but only if sales and Throughput are not blocked and only at the constraint – the factor that limits the businesses capability to produce Throughput. If a business has plenty of production capacity, then it may be that the efficiency of the sales organisation should be improved. How can more orders and market share be gained? Sometimes (often?) sales people are hampered in their efforts by the factory’s drive for efficiency! If a factory’s delivery performance in terms of lead-time and due date reliability is poor, no wonder sales have a hard time convincing customers to buy. Conversely, if all competitors’ performance is equally poor, then the one company that improves lead-time and due date performance significantly will almost certainly emerge as a winner. This company’s sales and margins will improve, at least until competitors catch up.

Engines of Disharmony

While I hope that all of the above might make sense to you, a lot of it is the opposite of common practice. In fact it is often the opposite of what managers and employees think is expected of them. In today’s business World there are constant pressures to improve – efficiencies must increase, costs must decline, inventories must be minimized, due date performance should be perfect and lead-times short. Almost everyone sees the conflicts between the first two (efficiency and cost) and the rest. People have no choice but to compromise. The 3 quotations in the box above indicate what many smart people think about the value of compromises.

In fact these diverging pressures lead to Goldratt’s “engines of disharmony”. These “engines” are:

- Not knowing my own required contribution to the goal or how my contribution will be measured and recognized.

- Not knowing others’ contribution or how their contribution should be measured and recognized.

- Organizational conflicts about which “rules” to use to best achieve organizational goal(s).

- Individual conflicts due to unresolved gaps between responsibility and authority (e.g. resulting in firefighting).

- Inertia or the fear of failure blocks necessary changes to achieve ongoing improvement.

Lets assume a manager (CEO) decides to implement the suggestions from above. Unless the reasons for the change are explained very well these engines are likely to be active and prevent the desired progress. If old rules are not modified correctly then despite good explanations the engines will be active – especially if many ‘old’ rules support the efficiency syndrome and pressures on cost. The rules need to change so that Throughput becomes the top priority (without making inventories and cost unimportant) not some unsatisfactory compromise between sales increases and cost reduction.

The engines of harmony the CEO and his company need to achieve are:

- Employees know exactly how they should contribute and how their contribution will be measured and recognized.

- Employees know exactly how others should contribute and how others’ contribution will be measured and recognized.

- Systematically align “rules” with goal of the organization (replacing local/short term optima with global optima rules).

- Systematically close gaps between responsibility and authority, using “firefighting conflicts” to trigger improvements.

- Processes, skills and culture are improved continuously by exposing inconsistencies and challenging basic assumptions.

To create harmony in an organization will require a considerable amount of thought by the CEO and his management team. Changes such as those suggested will cause uncertainty and resistance. Employees will evaluate management’s actions In relation to their experience and their personal criteria. Resistance to the changes can be expected. This resistance is caused by employees’ evaluations about the proposed changes – including all the misunderstandings, all the experience they have from the past and how they evaluate the proposed changes in relation to their person (“what is in it for me”). To prepare for the change management might look at the situation from the 4 quadrants of (resistance to) change.

- “The pot of gold” symbolizes the expected benefit (for everyone involved) the CEO and management see from the proposed change. (The company will become much more profitable with positive consequences for both employees and customers.)

- “The crutches” symbolize the potential damage that may be the consequence of the proposed change.

- “The mermaid” symbolizes what employees like about the current situation – it might simply be that they know exactly what to do in their job and as a result they are comfortable and do not want to change.

- “The crocodile” symbolizes the consequences of not making the proposed change. If we do not make the changes then competition will … (All major automobile manufacturers see Tesla electric cars as a crocodile and consequently are developing their own electric cars.)

These four perspectives of a change are important in order to build acceptance throughout the company. The ‘inventor’ of the change (the CEO) is likely to be focused on the pot of gold and may ignore the other quadrants – except as they relate to him. The CEO must not forget that his managers and employees also have 4 perceptions of the change and these perceptions will not necessarily be the same as his.

Summary

Major opportunities exist for CEOs to fulfil their mission. Current common practice tends to block companies from realising this potential. CEOs and their managers need to move away from efficiency and cost focus everywhere, to a strong focus on Throughput first. If they do they will soon realise the powerful effect gaining Throughput can haves on their bottom line (not to forget the impact on cost and efficiency!).

Not only are their opportunities for CEOs to achieve their mission, tools exist to help them think about and design their successful change strategy and implementation tactics. The tools are useful frameworks to think about the many consequences and how both customers and employees will perceive them.

CEOs and companies that successfully implement the suggested changes should expected significant jumps in performance – not just a few percentage points, but double digit ones. (When implementing their change a CEO and his employees should record their expected outcomes, check their results against these and take appropriate action as a result of any deviation(s))

[1] We mentioned production and R&D, however, the effect of too much work in process causes the same damage in other departments – sales often chases too many ‘skirts’ (potential customers) and, due to too much WIP, misses out with too many opportunities.

[2] Throughput = the rate at which we make money or Sales less Totally Variable Costs (usually just materials). Many times Throughput is called contribution margin. We use Throughput because contribution margin, can an often is, defined differently.

[3] The optimal level of work in process (WIP) cannot be determined deterministically – there are too many variables and too much uncertainty. Happily the peak area is relatively flat so a good enough guess at the level of WIP is the way to go. Just do not starve your resources with too little work. The risk of too little work for resources is small since a) only the constraint should be close to a full load and b) the efficiency paradigm will not disappear easily.

Technorati Tags: Cost, Cost Accounting, Costing, Efficiency, Finance, Focus, Goldratt, Key Performance Indicator, KPI, Little's Law, Management, Production, Shareholder Value Add, SVA, Theory of Constraints, TOC